Topic Index

The font size for a topic word is sized by the number of articles that reference that topic. The more articles the bigger the font.

Click on a word to search for posts with that topic. This page will reload with the search results.

Maccheroni alla Chitarra con Ragù d’Agnello

From Abruzzo comes Guitar Cut Pasta with Lamb Ragù

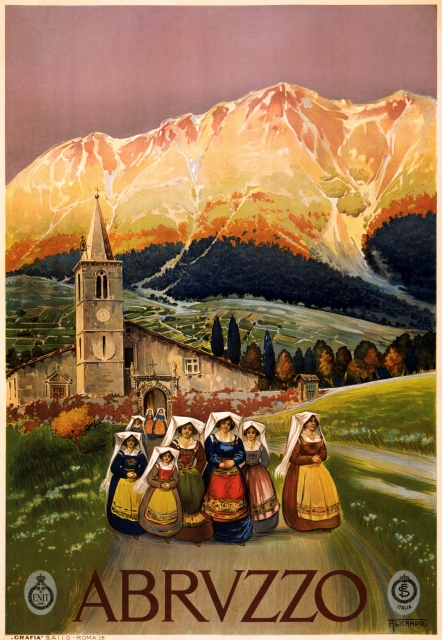

Abruzzo – from the majestic Gran Sasso to its beaches on the Adriatic Sea this part of Italy has postcard perfect terrain. To walk in the mountains of Abruzzo is to walk the age old route of the transumanza – the seasonal sheep migration, and indeed, sheep figure prominently in the socioeconomic history of this region and its cuisine.

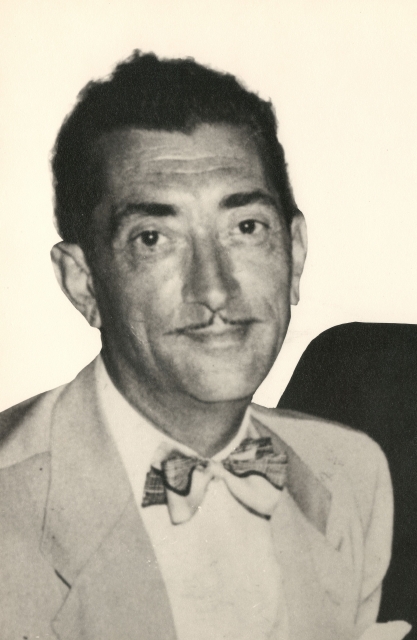

Gaetano Alfonso Crocetti

Born 1894 Montesilvano, arrived New York 1913, died 1967 Los Angeles, California

My grandfather, Gaetano Crocetti was born in Montesilvano, Abruzzo. He loved the food of his homeland, and although I have written previously about Ferratelle, the Abruzzese take on Pizzelle, this region has as its most singularly recognizable contribution to Italian cookery an implement known as the chitarra, a tool used to cut pasta. In her book Food and Memories of Abruzzo Anna Teresa Callen writes that this tool appears in manuscripts dating as far back as the thirteenth century.

Indeed la chitarra is part of Abruzzese culture, Read the remainder of this entry »

Italian Seeds

Italian cuisine is not all about pasta. Oh no. The Italians have a way with vegetables. And they grow their own. They have developed the most magnificent array, and now we in America can buy Italian seeds. Yes, now you can grow Italian. Each year I see more and more imported Italian vegetable and herb seeds at garden centers, but the go to place remains Seeds from Italy. The number of their offerings is astounding – more than thirty varieties of radicchio and chicory alone. And it just keeps getting better – by September they expect to have Italian garlic – Sulmona from Abruzzo and Berrentina Piacentina from Piacenza. The list goes on – beans, cabbages, kale, cavolo, caulifower, endive, escarole, and I’m only to E. My favorites, however are the pumpkins, le zucche. You’ll find a tremendous selection, and you have never seen ones like those grown from Seeds from Italy. The only thing you will regret once you peruse their catalogue of imported Italian seeds is that your backyard garden is not larger. Life is good in the garden. Start planning!

Note: You can click on any picture to see a slide show of even more pictures!

I have no affiliation with any product, manufacturer, or site mentioned in this article.

Ferratelle

Especially popular at Christmas, Easter and weddings, ferratelle are a classic Abruzzese treat. In other parts of Italy these delightful waffle cookies are known as pizzelle, nevole, catarrette, cancellette and more, but in Abruzzo where my grandfather Gaetano Crocetti was born they are known as ferratelle. The implements used to make the cookies first appeared in the late eighteenth century and were fashioned of iron, ferro in Italian – and the cookies were dubbed ferratelle. Lu ferro, as the iron is known, consists of two plates, most often rectangular, each attached to a long handle and secured with a locking mechanism. The inside of the plates, the side on which the cookies are baked, is etched with a grate-like design. Some say the name cancellette and the grate-like design were inspired by the screens in nunneries. Dough or batter is placed on one of the plates, the long handle locked closed and the plates held over an open fire. If you come across old ferratelle irons you may see initials, family insignias or names etched on the inside of one of the plates. It was customary for a family to have their own iron, often a prized wedding gift. They are beautiful tools, and after many years of use and thousands of cookies, the irons take on a stunning patina and wonderful non-stick finish, just like nonna’s cast iron frying pan. Should you be lucky enough to have an original etched iron, well then, I am envious. Very envious.

Nowadays most families have an electric ferratelle maker. They are sold in the U.S. as pizzelle makers, and they look like small waffle irons. Aluminum irons for stovetop and hearth use are also available. Both electric and stovetop types can be purchased at Amazon and many specialty shops. For an authentic iron you will need to make a trip to an antique store or nonna’s basement or attic.

Lots of cultures make a cookie like this, the most famous being the Norwegian Krumkake. Of course we are talking about Italy where the tradition of mille nonne is at work – a thousand grandmothers – a thousand recipes, and almost as many names. All ferratelle, or pizzelle, have four ingredients in common – flour, sugar, eggs, and some kind of fat – butter, olive oil, lard, vegetable oil, even margarine. From there the road diverges. The most common flavoring is anise, either ground seeds, oil or extract, and in widely varying amounts. I like just a hint almost more for aroma than taste, but some recipes call for much more. Use what ever amount pleases you, a recipe direction the Italians express as quanto basta, q.b.

Lots of cultures make a cookie like this, the most famous being the Norwegian Krumkake. Of course we are talking about Italy where the tradition of mille nonne is at work – a thousand grandmothers – a thousand recipes, and almost as many names. All ferratelle, or pizzelle, have four ingredients in common – flour, sugar, eggs, and some kind of fat – butter, olive oil, lard, vegetable oil, even margarine. From there the road diverges. The most common flavoring is anise, either ground seeds, oil or extract, and in widely varying amounts. I like just a hint almost more for aroma than taste, but some recipes call for much more. Use what ever amount pleases you, a recipe direction the Italians express as quanto basta, q.b.

I have seen recipes that call for cinnamon, cannella in Italian. Some add vanilla powder or extract, almond oil or extract, lemon or orange zest, oil or extract, or one of my favorites, Fiori di Sicilia. Fiori di Sicilia is a potent mix of orange, vanilla and jasmine, and is available from King Arthur. And since we are talking Abruzzo, source of some of the finest saffron (zafferano) in the entire world, when a cook really wants to splurge she will add some to the mix. For an extra depth of flavor I use brown butter, butter that has been heated to the point where it melts and the milk solids begin to brown. The amazing thing about brown butter is how something so simple to make can have such a complex flavor and add so much to a dish. Whether you put it on eggs, vegetables, fish or add it to a dessert, it brings a unique depth of flavor to any dish. I think of brown butter as a great ingredient that is less than five minutes away; if you’ve got butter, a saucepan and a burner, you’ve got brown butter. But let me emphasize – this step is my addition and in no way traditional, except in my kitchen. Feel free to skip it.

Here is a short clip on how to make brown butter.

These cookies are most often left flat, but they can also be molded right after baking. You can wrap them around cannoli tubes and fill them with whipped cream, pastry cream, Nutella, honey or other filling. You can also form them into cones by wrapping the still hot cookie around a wooden cone mold.

Ferratelle recipes produce every consistency from malleable doughs to loose batters and all points in between. My electric unit produces circular cookies, so I form the dough into balls. If you will be using a hand held iron, either at the stovetop or the hearth, I suggest you use a recipe that will produce a dough-like, or at least a paste-like consistency. The experience will be much more pleasant and much less messy than if you use a batter. And if you are using an iron with rectangular plates, tradition dictates that you form each piece of dough into rope and then into a figure eight to ensure even coverage of the cooking surface. And the cooking time for the hand held irons? Yield to tradition – for the first side say an Ave Maria, give the iron a flip, say a Pater Noster and the cookie is done. I just love Italian food.

Gently fold in flour mixture in three additions.

Ferratelle

makes about 30

1 3/4 cup all-purpose flour

1 stick (8 tablespoons) unsalted butter, browned and cooled

1/2 cup granulated sugar

2 large eggs plus 1 large egg yolk

1 packet (una bustina) of Vanillina* OR 1teaspoon vanilla extract

anise oil, q.b.

1 teaspoon baking powder

pinch kosher salt

This recipe will produce a malleable dough. These directions are for an electric unit.

Place a towel beneath the iron to capture any fat that may leak. Heat iron.

Brown the butter. Set aside. Watch my video to learn how to make brown butter, burro nocciola to the Italians.

In a small bowl combine flour, baking powder and salt. Set aside.

In a medium bowl beat eggs and sugar until light in color.

Add melted butter, vanilla and anise oil. Combine well.

Gently fold in flour mixture in three additions. Dough will come together in a firm ball.

Pinch off a tablespoon of dough and form into a ball. Repeat with remaining dough.

Place 1 ball of dough on each plate. Close and lock lid.

Bake until steam subsides, about 35 to 40 seconds, depending on your iron and on how brown you want your ferratelle. Remove to rack to cool. If you are going to form the ferratelle into cones or tubes, do so when they are hot.

Bake until steam subsides, about 35 to 40 seconds, depending on your iron and on how brown you want your ferratelle. Remove to rack to cool. If you are going to form the ferratelle into cones or tubes, do so when they are hot.

* I like to use Vanillina Pura, a vanilla powder manufactured by Fratelli Rebecchi. It is available at many Italian markets, and online at Amazon.

Note: You can click on any picture to see a slide show!

I have no affiliation with any product, manufacturer, or site mentioned in this article.

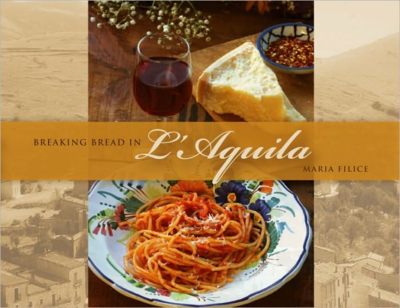

Breaking Bread in L’Aquila

Before dawn on the morning of April 6, 2009 the town of L’Aquila in Italy’s Abruzzo region was struck by a violent 6.3 magnitude earthquake, terremoto in Italian. Townspeople awoke in terror as the walls of their homes, businesses, government buildings and churches collapsed around them. The air was cold, but the people of L’Aquila ran outside to safety in whatever they had on to escape falling debris. When the sun shone on the town, the devastation was virtually complete. Rubble was everywhere. The dead were lined up in rows, and rescuers from the Abruzzo Civil Authority and Ministry of the Interior, along with the town’s inhabitants, worked feverishly to save those trapped and to remove the dead from the rubble. 308 people died that day. As of June 2010 Italian government statistics tell us that 48,810 people who lived in L’Aquila and surrounding villages are as yet unable to return home. The reconstruction effort continues.

Maria Filice, author and food stylist has written Breaking Bread in L’Aquila, a collection of 49 recipes from the Abruzzo region. Ms. Filice, whose family hails from the region of Calabria has a deep and abiding love for the Abruzzo region and L’Aquila in particular; her late husband Paul Piccone was born in that beautiful city, and the two traveled often to the region.

Ms. Filice has produced a wonderful volume. Its recipes are divided into days of the week with a complete menu presented for each day. Mix and match as you will. I certainly do. The author has generously included sections on how best to use her book, her entertaining philosophy and a primer on Abruzzese wines along with pantry essentials and a most welcome measurement conversion chart. The photography and food styling are ravishing, and the reader is given a warm and enticing introduction to this majestic region, land of shepherds and the sea. My grandfather, Gaetano Crocetti was born in Abruzzo in 1894, so this book holds pride of place on my shelf.

The net proceeds from the sale of this book will be donated to the L’Aquila earthquake restoration efforts. With Christmas around the corner I cannot think of a better gift for the cook or Italophile in your life. It would be a gift for two, whomsoever receives the book and the people of L’Aquila.

I am pleased to share with you, reprinted here courtesy of Telos Press, Paul Piccone’s recipe for polpettine, little meatballs. I have also included Maria’s charming introduction. She serves these with her Tomato Sauce and an Abruzzese specialty, pasta alla chitarra. The polpettine are delectable and simple to make. Enjoy, and please support L’Aquila earthquake relief by purchasing a copy of Maria’s book.

Click here to purchase the book at Food & Fate

Check out Maria’s blog here.

Take a look at the Breaking Bread in L’Aquila Facebook page here.

Follow Maria on Twitter @FoodandFate

Pasta alla Chitarra con Polpettine di Paolo

(Pasta alla Chitarra with Paul’s Meatballs)

Paul’s meatballs were famous-not only for their flavor, but also for their size: he liked them small! Though, he was a fabulous cook, once he let me in the kitchen (and taught me how to make his favorites), he didn’t come back in. As queen of the kitchen, I began making his favorites, like this one. We would sometimes serve these meatballs on top of pasta alla chitarra, Abruzzo’s famous pasta. This is made with a pasta guitar (it looks like a harp) to produce squarish-shaped spaghetti. You can also use spaghetti or your favorite pasta. Growing up, my mother would serve it with our favorite rigatoni or penne pasta.

serves 6

3 cups of tomato sauce (see page 44 in the book)

1 pound ground pork

1 pound ground beef

2 eggs

1 ½ cup freshly grated Parmigiano cheese

1 tablespoon fresh Italian flat leaf parsley, chopped

1 cup bread crumbs (unseasoned)

1 clove garlic, minced

½ teaspoon fresh ground black pepper

2 teaspoons salt

1 pound of pasta alla chitarra (fresh)

3 tablespoons extra virgin olive oil

In a large bowl, combine the pork, beef, eggs, bread crumbs and 1 cup of the cheese. Add the parsley, garlic, salt and pepper and combine well. Using your hands, form quarter-sized meatballs and place them on a tray. (If the mixture is too stick, rinse your hands under cold water and leave them slightly damp.)

Heat the oil in a frying pan over medium heat. Fry the meatballs in batches, turning them frequently, until they form a nice brown crispy layer on the outside and are cooked through (approximately 10 to 12 minutes). Drain them on paper towels.

Heat the tomato sauce in a medium-sized pot over medium heat. Add the meatballs and cook on low heat for 30 minutes.

Using a large pot, cook the pasta according to the package instructions until it is al dente. Drain the pasta and return it to the pot. Add the sauce with meatballs and toss well. Top with remaining Parmigiano and serve.

Mom’s Sauce

We called her Mom. Her full name was Angela Barra Crocetti. She was my paternal grandmother, and woe betide the individual who addressed her as such. It was Mom. Period. And her husband, Gaetano, well, we called him Pop. That’s just the way it was. Mom was born in Fernwood, Ohio in 1898. My grandfather, Gaetano Crocetti was born in 1894. He left his home town of Montesilvano in the region of Abruzzo, Italy and traveled to Naples in 1913. From there he boarded the Hamburg to sail to the United States of America, arriving at Ellis Island in September. Sponsored by his brothers, he went to live in Steubenville, Ohio, and in 1914 he married Angela Barra. Their firstborn, Guglielmo (William), my father, came into this world in 1916. And his brother Dino followed one year later. Mom was a terrific cook and a terrific grandmother. Uh oh, there’s that word again. She came to visit us, it seems, every day. I remember her driving up in her white Cadillac carrying an impossibly huge buff leather pocketbook. Now that was the treasure chest.

Read the remainder of this entry »