Topic Index

The font size for a topic word is sized by the number of articles that reference that topic. The more articles the bigger the font.

Click on a word to search for posts with that topic. This page will reload with the search results.

Biscotti di Nero d’Avola

The holidays are coming and it is time to think about tiny treats. For an afternoon snack, an accompaniment to an after-dinner glass of wine, or tidbits for surprise drop-in guests, these biscotti are perfect. These little cookies bear a distinct resemblance to Sicily’s famous Biscotti di Regina, but they have a lot more going for them. Not too sweet, they are made with olive oil rather than butter or shortening, and they are perfumed with Nero d’Avola, one of my favorite wines. Cinnamon and white pepper provide added warmth and depth of flavor, while accenting the spice notes of the wine. Read the remainder of this entry »

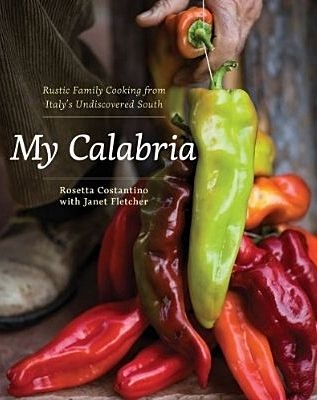

My Calabria by Rosetta Costantino with Janet Fletcher

A Book Review

My Calabria: Rustic Family Cooking from Italy’s Undiscovered South

I have mentioned it before. I am a cookbook addict, an avid collector. I love the genre, and my shelves are overflowing. Positively, absolutely overflowing. The truth is the books have begun a slow walk across the library floor, down the hall to the side of my bed. Ask anyone who knows me, and they’ll tell you. It is only fitting that the books have made their way to my bedside since cookbooks are my preferred bedtime reading. But with all those books I have had to become highly selective with my purchases. This one, however, was the proverbial no brainer. As soon as I heard that Rosetta Costantino had written a book on the cooking of Calabria, I knew I had to buy it. Ms. Costantino was born in Calabria, and at the age of fourteen came with her parents to the United States. She and her family live in Oakland, California where she teaches cooking. Her book was released late last year. I apologize to you all for keeping it to myself. Its 416 pages are filled with the food and culture of Calabria, all from the very personal viewpoint of Ms. Costantino. This collection of recipes, reminiscences and cultural background will have you reaching for your Post-It Flags. Read the remainder of this entry »

Il Festino di Santa Rosalia and The Black Plague

Yersinia pestis. The Plague, the Black Death, the Work of the Devil and God’s Retribution, the people of Palermo called it all that and more in 1624 when they were struck by a microbe whose name man did not yet know. As they prayed, built fires and collected the dead, they waited for the only help they knew, Salvation from Above. Salvation came in the form of a citizen’s fever dream, and Santa Rosalia was her name. Though dead for 400 years, “la Santuzza” appeared to one Sig. Bonello and directed him to retrieve her bones and carry them in a Grand Procession to all corners of the city. This he did, and the Plague abated. The Palermitani were saved, and a patron saint was born to Palermo. Read the remainder of this entry »

Gelatina di Nero d’Avola – Nero d’Avola Wine Gelatin

Bonnie, old friend and lover of all things Sicilian, this one is for you. This is one very adult homemade jello. Read the remainder of this entry »

Blood Orange Panna Cotta

So dramatic. So exotic. Winter in Sicily. Breakfast in the finest hotel. I am talking about blood oranges, Moro blood oranges in particular. Does any citrus make such a statement? This fruit will have you seeing red.

Cut a Moro open and see brilliant crimson throughout. Juice it and see an opaque liquid as dark as blood. Drink it and experience the marriage of orange with a hint of raspberry over a pedal point of tartness.

This is orange juice for adults. I figured that the juice, along with being a magnificent drink on its own, would be an unbeatable component in panna cotta. There are several kinds of blood oranges – Moro, Tarocco and Sanguinello being the most common. Although they all ripen in winter, the Moros ripen first and are at their peak right now. You can find them in Farmer’s Markets and many supermarkets these days. Lucky me, I find them in my back yard. I love my blood orange trees, but the Moro is my favorite – especially at this time of year. It is a wildly productive tree and now its branches are heavy with a medium sized fruit. The skin is quite rough and sports an enticing crimson blush. And, thank you Mother Nature, Moros are virtually seedless. If you would like your own blood orange tree, check out Four Winds Growers, a great source for hard to find citrus.

Let’s get to the recipe – for a step by step discussion of Panna Cotta and the proper use of gelatin, take a look at my recipe for Espresso Panna Cotta. You will find lots of explanations and photos there. I cooked up several versions – all cream, cream and milk, more milk than cream – more gelatin – less gelatin. I settled on 1 cup of cream and ½ cup of milk. All cream and the dessert was undeniably voluptuous, but the orange flavor was somehow masked, muted, while the 2 to 1 cream to milk ratio allowed for a pleasant creaminess and a startlingly clean orange flavor. I settled on 1 teaspoon of gelatin to allow for a softer set. If you prefer a firm set, go ahead and increase the gelatin to 1 1/4 teaspoons. This panna cotta is something of a trickster – its dusky rose hue belies a bright clean orange flavor. So get busy, find some Moro blood oranges, or any other variety, and make some Panna Cotta. A word about the choice of oranges. Not all blood oranges are created equal. Moros are much darker than the other varieties, so if you use Sanguinellos or Taroccos, your Panna Cotta will take on a lighter hue. The varieties vary in sweetness, you may have to adjust the sugar.

Blood Orange Panna Cotta

makes 4 servings, ½ cup each

1 cup heavy cream

1/2 cup whole milk

1/2 cup blood orange juice, preferably Moro

1/4 cup sugar

1 teaspoon gelatin

fresh berries and mint to garnish

Combine heavy cream, milk and sugar in medium sauce pan. Over medium heat, stir to combine and dissolve the sugar. Heat to scalding. Remove from heat. Meanwhile pour orange juice in small bowl and sprinkle gelatin over it. Set aside for 5 minutes to allow to soften. After gelatin has softened, pour the orange juice mixture into the scalded cream, stirring to combine thoroughly and dissolve gelatin. Pour through a fine strainer into a clean bowl. Place bowl over ice bath, stirring often to cool uniformly. Transfer mixture into serving glasses. Cover with plastic wrap and refrigerate at least 2 hours or overnight, until ready to serve. When ready to serve top panna cotta with fresh berries and mint.

Note: You can click on any picture to see a slide show!

Crostoli

“Mamma, Che buona!” My father William Anthony Crocetti, born Guglielmo, did not speak English until he went to grade school. So I have no doubt that was what he exclaimed every time he ate the crostoli his mother made in her kitchen at 319 South Sixth Street in their south end neighborhood of Steubenville, Ohio. I wasn’t there, but those were his words. Senza dubito. And I bet Dino echoed his big brother.

Italians have been making these treats for hundreds of years. A recipe even appears in Pellegrino Artusi’s seminal cookbook, L’Arte di Mangiar Bene (The Art of Eating Well), first published in 1891. Although these delightful pastry knots are the prototypical Carnevale indulgence, they are also served at Christmas, New Year’s and Easter. This type of dolci is called nastri delle suore (nun’s ribbons), but that would never do for Italy, a country whose inhabitants identify themselves by regional ties first and as Italians second. Twenty regions – more than twenty names. These treats are called galani or frittelle alla Venezia in Venice and the Veneto, crostoli in Friuli, cenci (rags and tatters) or donzelli (young ladies) in Tuscany, frappe in Umbria, sfrappole or lattughe (lettuces) in Emilia-Romagna, chiacchiere (gossips) in Lombardy, chiacchiere di suore (nun’s gossips) in Parma, bugie (lies) in Piemonte and gigi in Sicily. Da vero. Call them what you will, they are fried dough, and I love fried dough. Like my father, I grew up eating these deep fried delights.

We called my grandmother Mom, and no typical nonna was she. When she arrived at our home I could always tell if she had a treat for us; instead of exiting her car and making her way directly up our driveway she went first to her passenger door, opened it and removed a long flat box. Then up our driveway she walked, box in hand, the clack-clack-clack of her Spring-o-lator shoes announcing her approach. We never knew what she had in that box, but we always knew it would be good. We four kids, my brothers Guy and Marc and my sister Toni and I, loved the cookies and we gobbled them up. My mother could always tell who had done most of the gobbling – the powdered sugar on the guilty party’s hands, face and chest was a dead giveaway. In fact that is how these cookies got their Piemontese name, bugie – liar’s cookies – as in “No Mamma. It wasn’t me, no mamma. I don’t know who ate the cookies…” Another of this cookie’s colorful names is chiacchiere or gossips. Some say the name came from the ladies of Lombard and the nuns of Parma who ate them as they gossiped. Still another source tells us the name originated with the sound the knots make when dropped in the cooking oil – “Pssst !” – just like the town gossip as she summons her listeners. Great stories all, which ever is true.

This cookie has a variation for every nonna. Some call for grappa, others get their alcohol kick from Gran Marnier, vin santo, white wine or rum while a few eschew spirits altogether. In Tuscany they are often made with olive oil in place of butter, and some regions use lard or shortening. Some use orange in place of lemon or no citrus at all. For the finishing touch, some cooks use confectioner’s sugar while others choose cinnamon sugar. As to the shape, some are plain ribbons, some are formed into pretzel-like shapes while others are twisted and pinched in the middle. You will also find flat squares or rectangles, some with one or two slits along the middle. This is the tradition of Italy’s beloved nonne at work, the tradition of variation on a theme that makes this cuisine so inviting, so forgiving, and so much fun.

Flour in Italy is classified by how finely it is milled, either 1, 0 or 00. Doppio zero is the most finely milled and feels like talcum powder. Do not confuse how finely ground the flour is with its protein content. Any strength flour can be ground into doppio zero. Just as we have pastry flour, all-purpose flour and bread flour with their varying protein contents, so do the Italians. They just have the added luxury of varying degrees of milling. To see the full range of flours available to the Italian cook go to the Molino Caputo website. I use a doppio zero flour that is comparable in protein content to our American all-purpose flour. Doppio zero flour is available at Italian markets and Amazon. com. If you can not find it, regular all-purpose flour will do nicely. Use the same amount the recipe calls for.

Mom made her dough by hand in the traditional manner – mounding her flour on a wooden board, making a “well” in the center, filling it with the ingredients and incorporating them with a fork. In a concession to the age of the mechanized kitchen I use my KitchenAid.

This dough is a dream to work with. Do not be intimidated by the idea of rolling it very thinly. You will be able to do so with great ease. Honest. On the subject of frying oil – Mom used solid Crisco, and there is no reason to change that. But if you have something else on hand, peanut oil, vegetable oil, feel free to make use of what is in your pantry. Mom drained the cookies on brown grocery bags. Some cooks use paper towels. I have found that placing the fried cookies directly on a cooling rack suspended over a sheet pan works very well.

A note about these cookies: they fry up very quickly, so be sure to have everything you need close at the ready. Banish the kids and pets from the kitchen. You will be working with a large volume of very hot oil.

And finally, do not overcook the crostoli. If you do you will not taste the grappa!

As the Italians say “Divertiti!” Have fun!

Form knots and place on a floured tea towel.

To keep things neat, place your tray and rack on a large piece of parchment. Have ready a bowl of confectioner's sugar and a small strainer.

Crostoli

makes about 3 ½ dozen

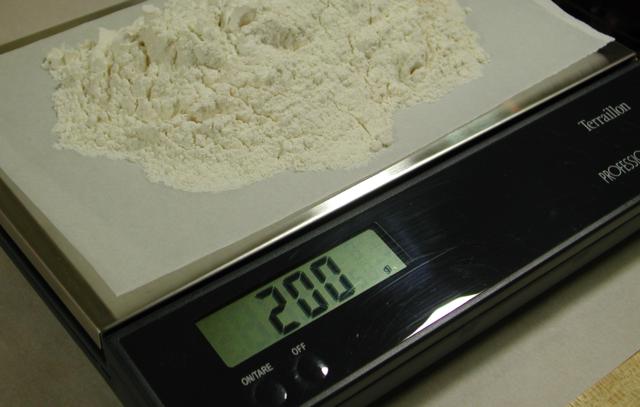

200 grams 00 flour (This should measure 1 ½ cups when lightly spooned into measuring cups, then leveled with a flat edge.)

1 tablespoon granulated sugar

zest of 1 lemon

generous pinch salt

1 large egg, lightly beaten

1 tablespoon unsalted butter, at room temperature

1 tablespoon grappa

1 teaspoon vanilla extract

3 to 4 tablespoons whole milk

shortening or oil for frying

confectioner’s sugar

In a mixer bowl fitted with paddle attachment, combine the flour, sugar, lemon zest and salt. With mixer running add egg, butter, grappa and vanilla. Gradually add 3 ½ tablespoons of milk to form a soft malleable dough. Remove dough from bowl, pat into a disk. Wrap in plastic, and set aside to rest for 1 hour.

Line a sheet pan or tray with a tea towel. Lightly dust the towel with flour. Set aside. Divide dough in 2 pieces, keeping the one you are not using wrapped in plastic or covered with a towel. On a lightly floured board, roll out dough as thinly as you can, about 1/16-inch thickness; dough should be almost translucent. Using a ravioli cutter cut dough to form ribbons 6 inches long and 1 inch wide. Tie a knot in the center of each ribbon, and place on the towel-lined pan in a single layer. Keep the knots covered as you work.

Meanwhile heat a generous amount of oil to 350 degrees in a heavy deep-sided pan. A candy thermometer placed on the side of your pan assures correct cooking temperature. Have ready a rack placed over a sheet pan. Fry the knots, a few at a time, until they color, about 20 to 30 seconds. Remove with a slotted spoon, spider or metal tongs, and place on rack to drain. Sprinkle liberally with confectioner’s sugar. Crostoli are best eaten the day they are made.

Note: You can click on any picture to see a slide show!