Topic Index

The font size for a topic word is sized by the number of articles that reference that topic. The more articles the bigger the font.

Click on a word to search for posts with that topic. This page will reload with the search results.

Dad’s Favorite Dishes

Pasta Fazool. Pasta Fazoo. Pasta fa Zuole. Pasta e Fagioli. Italians call it a lot of things. My dad, Bill Crocetti, called it delizioso. He used to make his own. Nope, this dish was not entrusted to my mother. Uh uh. Funny how you can want a dish just so. That is when you have to make it yourself. So at the stove stood my dad cooking up a memory of his childhood. Now, as an adult I understand the contented look on his face as he breathed in the perfume of the garlic cooking in the olive oil, his olfactory senses transporting him back to his childhood kitchen over his father’s barbershop in Steubenville, Ohio. That is how it was for my dad where Pasta e Fagioli was concerned. As far as I can remember it was all his, start to finish. To me as a kid, I thought it an odd, unattractive dish. The garlic, the oil, the parsley, the tiny little pasta, I wanted something red in there. Give me tomatoes, Daddy, please! Well, then it would not have been his Pasta Fazool. Yes, it is that simple. Again the tradition of mille nonne, a thousand grandmothers, is at work. No two families make it the same way. Period. Some cooks use crushed or canned tomatoes in their Pasta e Fagioli – in the heart of the Mezzogiorno the broth is kissed with a dollop of tomato paste giving it a slightly pinkish hue. My dad preferred just a bit of pasta water, so little it was not a soup, but rather a hearty bean and pasta dish. Even within my dad’s family there were variations. His brother preferred a version more akin to a soup with a tomato base. Not so my father. It was beans and pasta. Pasta Fazool. That’s what he called it, and that is what it was. And the pasta, well that depended on what was in the cupboard. It could be ditalini, maybe elbow macaroni, maybe orecchiette, maybe tubetti. It was cucina d’opportunita – use what you have. Another of his specialties was Spaghetti Aglio e Olio, Spaghetti with Garlic and Oil. This is simple food straight from the south of Italy, and along with dishes like Pasta e Fagioli and Cacio e Pepe, is man food, the kind of dishes men cooked up when left by themselves. My dad’s Aglio e Olio was classic. He poured olive oil into a frying pan. (We never called it a skillet and certainly not a saute pan. We’re talking the fifties here.) He sliced the garlic, lots of it, tossed it in the pan and let the whole thing heat up, cooking the garlic just until it was golden, the oil shimmering around it. Meanwhile a pound of spaghetti cooked on the next burner. Just before the pasta was done, and the garlic was just golden, he carefully poured some of the pasta water into the frying pan and let it boil a bit. I always stood back because, boy, did it ever bubble up. A quick draining of the pasta and into the frying pan it went, along with the parsley. A bit of tossing, a bit more heat, lots of parmigiano, and he was ready to eat.

My dad was happy in front of the stove. He made all manner of delights including the best fried eggs, uove frittellate, ever. His secret? Butter. Lots of butter and a lid for the frying pan. He put a half stick of salted butter in a small but well used Revereware frying pan, let the butter get spitting hot and slid in the eggs. A little salt and pepper and he was on his way. The sweet smell of butter cooking filled the kitchen. To this day I still love that smell. The yolks retained their gorgeous deep yellow color while the whites were utterly transformed. Little bubbles formed and then burst around the edges of the whites leaving behind a network of crispy brown lace that gave his eggs a distinctive crunch. He took a peek at the underside of the eggs, and if it had begun to brown, that’s when he put the lid on. Yup. The lid went on. It trapped the steam in the pan and finished cooking those glorious eggs. Oh, how I used to love it when he fried eggs for the two of us.

I was talking to my sister Toni the other day and the conversation turned to dad’s uove frittellate. Imagine my surprise as she spoke of the dish as though it were the sole province of her and dad. I thought it belonged to me and dad! Not until we had that conversation did I realize that he had ever made those eggs for anyone but me. He could make each of us feel like a princess while avoiding the trap of making the other daughter feel like a peasant. What a dad.

I was talking to my sister Toni the other day and the conversation turned to dad’s uove frittellate. Imagine my surprise as she spoke of the dish as though it were the sole province of her and dad. I thought it belonged to me and dad! Not until we had that conversation did I realize that he had ever made those eggs for anyone but me. He could make each of us feel like a princess while avoiding the trap of making the other daughter feel like a peasant. What a dad.

It was just so much fun to share food with him. Fried kidneys were our project from start to finish. No one else in our family was interested. Not in the least. They scattered, and we drove to the market together, asked the butcher for some kidneys and back home we came. The flavor and perfume of fried kidney is the rara avis of the culinary world. Unmistakable. I won’t attempt to describe it here. No one could do it better than James Joyce. But my dad was always able to make them without that je ne sais quoi Joyce so skillfully describes. I can still see the kidneys glistening in their wrapping, their burgundy fullness holding promise of delights to come. He sauteed them in butter, and I consumed them with gusto. And then one day I learned kidneys were “an organ,” and that was the end of the affair. In short order liver was also off my list. My dad, quite exasperated by my sudden refusal to eat organ meats asked my why. I replied “Because they are organs, Daddy. ” He looked at me and sternly said “Well, Adri a steak is a muscle.” Dead silence ensued. He realized he had made a fatal error. The very serious look on my face as I quietly ruminated on his pronouncement must have told him what was coming next. Adri, The Picky Eater was born, my gustatory adventures severely curtailed. As time went on, steak returned to my menu, but alas, kidneys never did. I bet my dad missed our kidney fests.

Pasta e Fagioli

1 15 oz. can cannellini beans, rinsed

1/4 pound small pasta, such as orecchiette, pennette, tubetti, or elbows

2 tablespoons olive oil, plus more to finish

3 oz. pancetta, diced

2 cloves garlic, minced

generous pinch oregano

pinch red pepper flakes

1/4 cup chopped parsley

Parmigiano

Drain and rinse the cannellini beans. Set aside.

Bring a large pot of water to the boil. When it comes to the boil, generously salt the water and add pasta.

Meanwhile, pour 2 tablespoons of olive oil into a large saute pan. Cook diced pancetta over medium heat until it is crispy and brown. Just a moment before the pancetta is done, reduce heat slightly, add garlic, oregano and red pepper. Saute very briefly, until fragrant.

Add beans, pasta and parsley to the saute pan, tossing gently to coat, adding pasta water, if necessary, to loosen the mixture.

Turn the mixture in to a serving bowl. If desired, toss with a tablespoon of olive oil. Serve immediately with Parmigiano or Romano.

How to cook spaghetti

For one pound of spaghetti, or other long pasta fill a stockpot, pasta pentola or other large cooking vessel with at least 6 quarts of water, and bring to a rapid boil. Once the water has come to the boil, add a generous dose of sea salt, about 1 teaspoon per quart of water. As the saying goes “The water should taste like the Mediterranean sea.” When the salt is added, the water will bubble up, so do exercise caution. The water will come off the boil, but will shortly return. Once the water has returned to the boil, add your pasta to the pot. Do not break it. As it softens, use a wooden spoon or other utensil to push it down into the pot. Again, the water will have come off the boil. Cover the pot until it returns to the boil. Once it has begun to boil again, uncover the pot, stirring occasionally, until just al dente. Remember, the manufacturer’s cooking guidelines are only suggestions; taste the pasta occasionally, being sure it is no longer white in the center and is the consistency you desire.

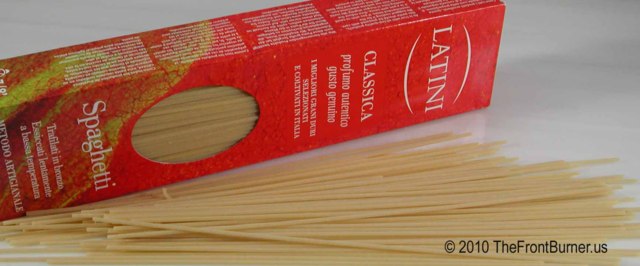

My favorite brands of dried pasta are Latini and Rustichella d’Abruzzo. They are premium products and can cost upwards of $6.00 for one pound of spaghetti. Pricey, for sure. For a more affordable and very good product I turn to Del Verde, De Cecco and Barilla.

Premium pastas such as Latini and Rustichella d’Abruzzo are set apart by their use of high quality wheat, in some cases heirloom strains, and the use of bronze dies in the extruding machines. The dies impart a uniquely rough texture to the pasta’s exterior. Because the rough exterior allows the pasta and sauce to bind so well, it is a particularly good conveyor of the taste of the olive oil, a key ingredient in Aglio e Olio. Use of the bronze dies coupled with low temperature, long drying times combine to make these artisan pastas unique. I can’t imagine what my dad would have thought of using such expensive pastas for these two supreme examples of cucina povera. But today these dishes have been elevated far beyond the level of cucina casareccia, home cooking. For that matter I can just see that wry smile of his were he to look at a menu from any of today’s tony Italian eateries and see Aglio Olio, Cacio e Pepe or Pasta e Fagioli listed. “Ain’t that a kick in the head,” he’d say.

Spaghetti Aglio e Olio

Olive oil takes center stage here. Be sure to use a good quality oil whose taste you really like. And go ahead – splurge on Parmigiano Reggiano, the pride of Italy. The cheese is manufactured to exacting standards in the Italian provinces of Parma, Reggio Emilia, Modena, Mantua and Bologna. Milk from local cows, whose diet is also regulated is used to make the cheese. You can be sure you are getting the real thing by looking at the rind of the cheese and making sure you see Parmigiano Reggiano in a repeating pin dot pattern.

1 pound spaghetti

1/4 cup extra-virgin olive oil, plus more to finish

3 or 4 large garlic cloves, thinly sliced

1/4 to 1/3 cup chopped parsley, to taste

1 cup grated Parmigiano-Reggiano, plus more for the table

Bring a large pot of water to the boil. Generously salt the boiling water and drop the spaghetti in. Do not break the spaghetti.

Pour oil into a saute pan. Set pan over medium heat and add garlic. Cook it gently, being careful it does not scorch or burn. If it burns, you must discard the contents of your pan and begin again. There is no salvaging burned garlic.

When the garlic is golden, add a cup of pasta water and boil to reduce it a bit. Be careful, water into hot oil splatters. Just before the pasta is done cooking add all of it to the saute pan along with the parsley. Cook gently, a minute or two, until the pasta is done, adding more pasta water if necessary to form a sauce that coats all the pasta. If it is too dry add a bit of pasta water, if there is too much water, increase the heat and reduce until it is the desired consistency.

Remove pan from heat, add cheese and a bit of olive oil, toss and serve at once.

Spaghetti Cacio e Pepe

The assertive flavors of the Pecorino Romano and cracked peppercorns combine to make this simple dish greater than the sum of its parts. Pecorino is a ewe’s milk cheese (pecora is Italian for sheep), and is part of a group of cheeses formerly known as Cacio. It is lighter in color than other Italian grating cheeses, quite sharp and leans to the salty side. It is also one of the oldest cheeses produced in Italy.

1 pound spaghetti

1-2 tablespoons crushed black peppercorns

1 cup freshly grated Pecorino Romano, plus more for the table

Bring a large pot of water to the boil. Generously salt the boiling water and drop the spaghetti in. Do not break the spaghetti.

Meanwhile grind the peppercorns very coarsely. If you do not have a pepper grinder, crush the peppercorns with a saute pan, meat mallet or mortar and pestle.

Warm up a large pasta bowl. When the spaghetti is al dente, lift it from the pot, drain very briefly and put it in the warm pasta bowl. Quickly toss the pepper and 1 cup of cheese with the pasta, adding a bit of pasta water to help combine the ingredients.

Serve the pasta straightaway, with more cheese and pepper on the side.

Note: You can click on any picture to see a slide show!

Crostoli

“Mamma, Che buona!” My father William Anthony Crocetti, born Guglielmo, did not speak English until he went to grade school. So I have no doubt that was what he exclaimed every time he ate the crostoli his mother made in her kitchen at 319 South Sixth Street in their south end neighborhood of Steubenville, Ohio. I wasn’t there, but those were his words. Senza dubito. And I bet Dino echoed his big brother.

Italians have been making these treats for hundreds of years. A recipe even appears in Pellegrino Artusi’s seminal cookbook, L’Arte di Mangiar Bene (The Art of Eating Well), first published in 1891. Although these delightful pastry knots are the prototypical Carnevale indulgence, they are also served at Christmas, New Year’s and Easter. This type of dolci is called nastri delle suore (nun’s ribbons), but that would never do for Italy, a country whose inhabitants identify themselves by regional ties first and as Italians second. Twenty regions – more than twenty names. These treats are called galani or frittelle alla Venezia in Venice and the Veneto, crostoli in Friuli, cenci (rags and tatters) or donzelli (young ladies) in Tuscany, frappe in Umbria, sfrappole or lattughe (lettuces) in Emilia-Romagna, chiacchiere (gossips) in Lombardy, chiacchiere di suore (nun’s gossips) in Parma, bugie (lies) in Piemonte and gigi in Sicily. Da vero. Call them what you will, they are fried dough, and I love fried dough. Like my father, I grew up eating these deep fried delights.

We called my grandmother Mom, and no typical nonna was she. When she arrived at our home I could always tell if she had a treat for us; instead of exiting her car and making her way directly up our driveway she went first to her passenger door, opened it and removed a long flat box. Then up our driveway she walked, box in hand, the clack-clack-clack of her Spring-o-lator shoes announcing her approach. We never knew what she had in that box, but we always knew it would be good. We four kids, my brothers Guy and Marc and my sister Toni and I, loved the cookies and we gobbled them up. My mother could always tell who had done most of the gobbling – the powdered sugar on the guilty party’s hands, face and chest was a dead giveaway. In fact that is how these cookies got their Piemontese name, bugie – liar’s cookies – as in “No Mamma. It wasn’t me, no mamma. I don’t know who ate the cookies…” Another of this cookie’s colorful names is chiacchiere or gossips. Some say the name came from the ladies of Lombard and the nuns of Parma who ate them as they gossiped. Still another source tells us the name originated with the sound the knots make when dropped in the cooking oil – “Pssst !” – just like the town gossip as she summons her listeners. Great stories all, which ever is true.

This cookie has a variation for every nonna. Some call for grappa, others get their alcohol kick from Gran Marnier, vin santo, white wine or rum while a few eschew spirits altogether. In Tuscany they are often made with olive oil in place of butter, and some regions use lard or shortening. Some use orange in place of lemon or no citrus at all. For the finishing touch, some cooks use confectioner’s sugar while others choose cinnamon sugar. As to the shape, some are plain ribbons, some are formed into pretzel-like shapes while others are twisted and pinched in the middle. You will also find flat squares or rectangles, some with one or two slits along the middle. This is the tradition of Italy’s beloved nonne at work, the tradition of variation on a theme that makes this cuisine so inviting, so forgiving, and so much fun.

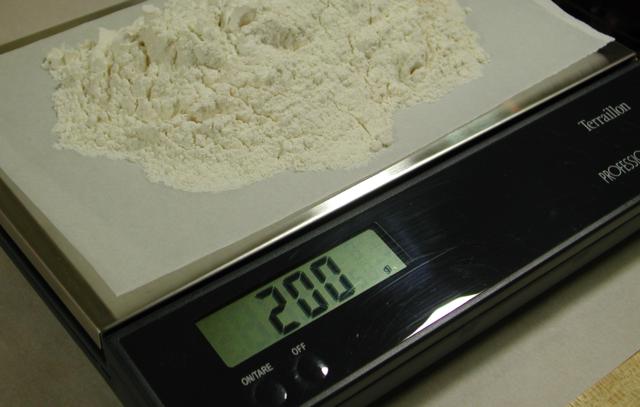

Flour in Italy is classified by how finely it is milled, either 1, 0 or 00. Doppio zero is the most finely milled and feels like talcum powder. Do not confuse how finely ground the flour is with its protein content. Any strength flour can be ground into doppio zero. Just as we have pastry flour, all-purpose flour and bread flour with their varying protein contents, so do the Italians. They just have the added luxury of varying degrees of milling. To see the full range of flours available to the Italian cook go to the Molino Caputo website. I use a doppio zero flour that is comparable in protein content to our American all-purpose flour. Doppio zero flour is available at Italian markets and Amazon. com. If you can not find it, regular all-purpose flour will do nicely. Use the same amount the recipe calls for.

Mom made her dough by hand in the traditional manner – mounding her flour on a wooden board, making a “well” in the center, filling it with the ingredients and incorporating them with a fork. In a concession to the age of the mechanized kitchen I use my KitchenAid.

This dough is a dream to work with. Do not be intimidated by the idea of rolling it very thinly. You will be able to do so with great ease. Honest. On the subject of frying oil – Mom used solid Crisco, and there is no reason to change that. But if you have something else on hand, peanut oil, vegetable oil, feel free to make use of what is in your pantry. Mom drained the cookies on brown grocery bags. Some cooks use paper towels. I have found that placing the fried cookies directly on a cooling rack suspended over a sheet pan works very well.

A note about these cookies: they fry up very quickly, so be sure to have everything you need close at the ready. Banish the kids and pets from the kitchen. You will be working with a large volume of very hot oil.

And finally, do not overcook the crostoli. If you do you will not taste the grappa!

As the Italians say “Divertiti!” Have fun!

Form knots and place on a floured tea towel.

To keep things neat, place your tray and rack on a large piece of parchment. Have ready a bowl of confectioner's sugar and a small strainer.

Crostoli

makes about 3 ½ dozen

200 grams 00 flour (This should measure 1 ½ cups when lightly spooned into measuring cups, then leveled with a flat edge.)

1 tablespoon granulated sugar

zest of 1 lemon

generous pinch salt

1 large egg, lightly beaten

1 tablespoon unsalted butter, at room temperature

1 tablespoon grappa

1 teaspoon vanilla extract

3 to 4 tablespoons whole milk

shortening or oil for frying

confectioner’s sugar

In a mixer bowl fitted with paddle attachment, combine the flour, sugar, lemon zest and salt. With mixer running add egg, butter, grappa and vanilla. Gradually add 3 ½ tablespoons of milk to form a soft malleable dough. Remove dough from bowl, pat into a disk. Wrap in plastic, and set aside to rest for 1 hour.

Line a sheet pan or tray with a tea towel. Lightly dust the towel with flour. Set aside. Divide dough in 2 pieces, keeping the one you are not using wrapped in plastic or covered with a towel. On a lightly floured board, roll out dough as thinly as you can, about 1/16-inch thickness; dough should be almost translucent. Using a ravioli cutter cut dough to form ribbons 6 inches long and 1 inch wide. Tie a knot in the center of each ribbon, and place on the towel-lined pan in a single layer. Keep the knots covered as you work.

Meanwhile heat a generous amount of oil to 350 degrees in a heavy deep-sided pan. A candy thermometer placed on the side of your pan assures correct cooking temperature. Have ready a rack placed over a sheet pan. Fry the knots, a few at a time, until they color, about 20 to 30 seconds. Remove with a slotted spoon, spider or metal tongs, and place on rack to drain. Sprinkle liberally with confectioner’s sugar. Crostoli are best eaten the day they are made.

Note: You can click on any picture to see a slide show!